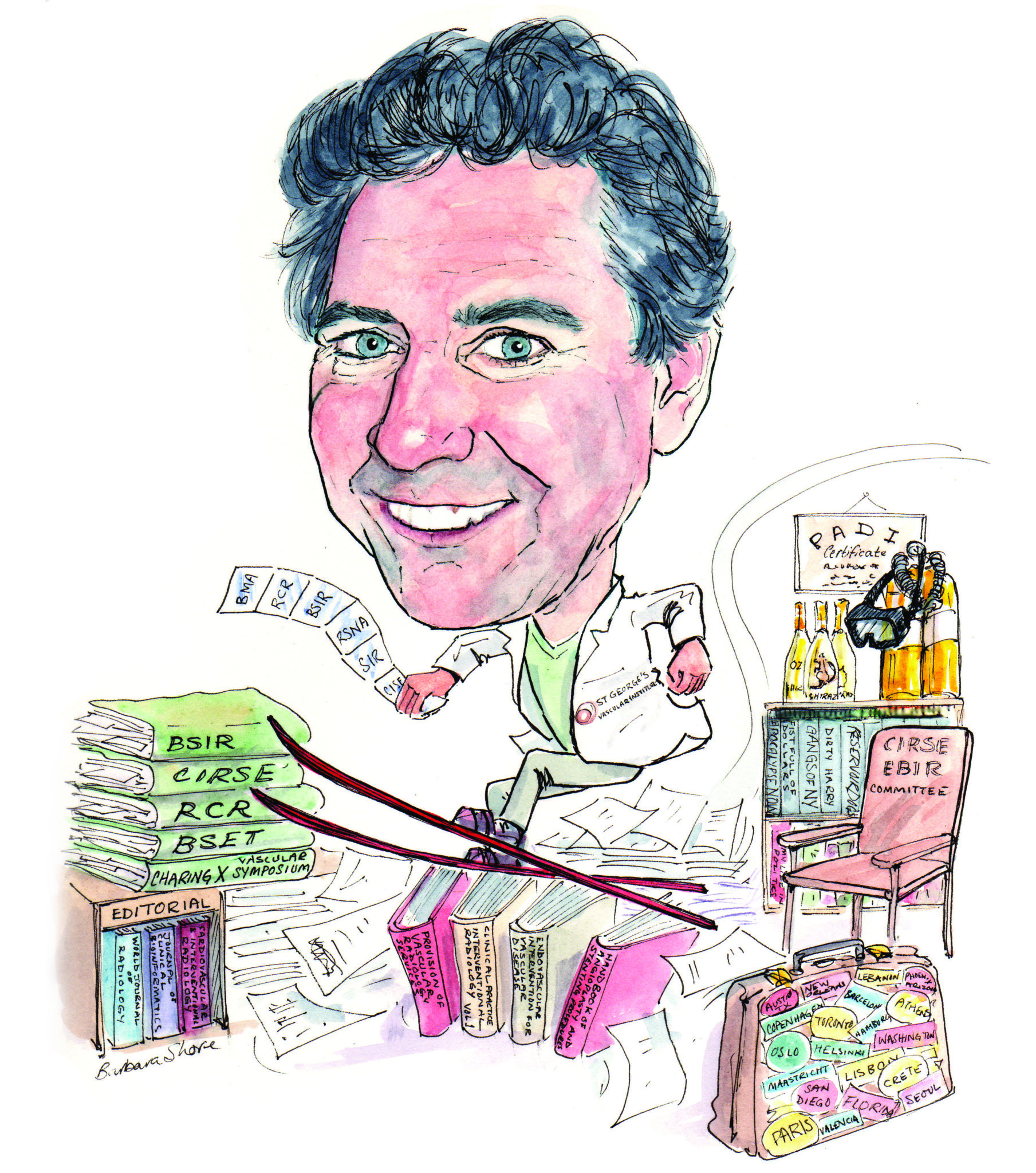

Robert Morgan, consultant vascular and interventional radiologist, St George’s Hospital, London, chairman of the CIRSE EBIR committee and a deputy editor on CVIR, told Interventional News that it was important to obtain formal qualification in interventional radiology to protect patients and that a table was worth a thousand words for those seeking to publish their work.

Can you describe your journey into interventional radiology?

During my early years, after qualification as a doctor, I was attracted into radiology by the exciting new procedures radiologists started performing such as angioplasty and stent procedures in the vascular, biliary and urological systems. From day one as a radiology trainee, I intended to be an interventional radiologist. After five years of radiology training, I went to University of Texas Medical Branch, USA, to undertake a fellowship in IR working for Eric vanSonnenberg. Initially intending to be a hepatobiliary interventional radiologist, I soon realised that my interests lay mainly in the vascular system. After staying a further year in Texas as a member of the IR staff, I returned to the UK and worked as a lecturer in IR for Andy Adam at Guy’s and St Thomas’s hospitals for 18 months, before taking up a consultant post in IR at St Mary’s NHS Trust, London.

Which innovation in IR shaped your career the most?

My two main areas of interest are the role of endografting for diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta, and the role of IR in the management of lower limb arterial occlusive disease. Therefore, I guess you might say that the main innovations were the advent of bare metal stents and endografts for use in the arterial system, including the aorta.

Who do you regard as your mentors in IR, and what advice of theirs do you carry with you, even today?

Andy Adam has always been a major influence in my IR career. I was always impressed with his mantra that anything can be achieved if you have the will and energy to see it through. Other major influences in making me what I am today are Irving Wells in Plymouth who first taught me how to perform angiography, and Eric vanSonnenberg and Eric Walser (also from UTMB, Texas), who never failed to surprise me with new approaches to a thorny clinical problem.

Could you describe a memorable case, and how IR came to the rescue?

Earlier this year, I treated a patient who illustrates the importance of interventional radiology and how as IRs, we can save patients’ lives. A 23-year-old medical student’s wife had a severe torrential postpartum haemorrhage and after losing 23 units of blood, her obstetricians were losing the battle to stop the bleeding and maintain her perfusion. On a Friday night, I was called back to the hospital to perform emergency angiography and embolisation. She arrived in the angiography department, with a blood pressure of 50/0 and close to cardiac arrest. Pelvic angiography immediately identified the two sites of active haemorrhage in branches of her internal iliac arteries. As her condition was so critical, it was necessary to inflate a balloon in the aorta to reduce the rate of bleeding. With her condition stabilised temporarily, after selectively catheterising the arteries supplying the bleeding points, I embolised the vessels with coils. The procedure took less than an hour. Her condition improved and she experienced no further bleeding. She was discharged from hospital five days later. I am in no doubt that without interventional radiology, she would have died.

IR in the UK has just received subspecialty status. What does this mean for the field?

It is a very important development, which will help considerably to promote the importance of interventional radiology and interventional radiologists to our patients, in our hospitals, in our relationship with our clinical colleagues, and finally in our discussions and negotiations with our political masters.

As the deputy editor of CVIR, what writing tips would you give to interventionalists who are looking to submit their work for publication?

The most commonly submitted articles to most journals are case reports. While sometimes interesting, few are truly unique, and there is a trend to reduce the numbers of case reports published in CVIR. In general, interventionalists would be much better off devoting their time to producing scientific papers based on a research project. Articles should be well-written without excessive verbiage. “A table is worth 1,000 words” is an old saying, and is very true! In my opinion, results should be presented in tabular form, if possible. Finally, do not make your article excessively long. Brevity is best!

Is it true that researchers nowadays break up their work into “bite-sized” publishable chunks in order to gain more publications?

This is an unfortunate trend worldwide, which, as the Reviews Editor for Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology, one has to be aware of and to restrict, if at all feasible. It is a practice that should be discouraged if at all possible, although in reality it is difficult to police.

The first EBIR exam has just taken place—how many people took part, and what is the importance of this qualification?

The European Board of Interventional Radiology (EBIR) examination was launched at the recent CIRSE congress in Valencia, Spain. Twenty candidates sat the first inaugural examination. We plan to hold examinations in Vienna next March, and at the CIRSE congress in Munich in September 2011. Further examinations are already planned to follow the Munich congress as part of an ongoing commitment to enable all IRs who want to take the examination to achieve the EBIR qualification as quickly as possible. The EBIR qualification is important because it is envisaged that it will rapidly become a recognised benchmark of quality, indicating that interventional radiologists holding the EBIR certificate have achieved the level of knowledge and ability required to practise as IRs in Europe.

How do you think IRs should arm themselves to protect patients from other specialities (who are perhaps not adequately trained) who are carrying out IR procedures?

The procedures that interventional radiologists developed are coveted all over the world by other specialities, who wish to perform these procedures, and think they have the right to do so, despite the total absence of structured training. One hears frequent stories about patients who are harmed by non-IR doctors performing established IR procedures without any formal training. For example, gynaecologists may start performing uterine fibroid embolisation, without undergoing formal training in IR, and rename themselves “interventional gynaecologists”, similarly we hear about “interventional neurologists” performing carotid artery stenting and intracranial thrombolysis, and “interventional nephrologists” performing dialysis fistula interventions. The list is almost endless. IRs can protect themselves from this incursion into their territory by admitting patients to their own beds, undergoing recognised IR training, and undertaking formal certification in interventional radiology. This is one of the main reasons the EBIR certificate has been introduced.

What are the current techniques and technologies that you are watching closely?

Branched endograft technology for the treatment of thoraco-abdominal aneurysms is an exciting, relatively new, treatment that will probably replace open surgery for this condition. Similarly, the final frontier for branched endograft usage is the ascending aorta and aortic arch. Although extremely challenging, I think we will see a workable solution to this conundrum in the next five to ten years.

What fascinates you about interventional radiology even today?

Despite all of the procedures that IRs have introduced to the medical world in the last 30 years or so, I never fail to be amazed at the continuous stream of new innovations which we see on an annual basis. Life is never dull as an interventional radiologist!