Malignant ureteric obstruction (MUO) poses several tangible threats to cancer patients—and these threats translate, in turn, to challenges for the interventional radiologist and other treating physicians. Here, Conrad von Stempel and Tim Fotheringham (University College LondoN Hospitals and Barts NHS Foundation Trusts, London, UK) describe a number of alternative techniques to common approaches via percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) or with polymeric JJ stents, while also assessing currently available evidence in this space.

Ureteric obstruction is a common sequela of genitourinary and other malignancies. Obstruction occurs from direct tumour infiltration, extrinsic compression from lymphadenopathy or tumour mass, and can occur because of malignant fibrosis or surgery. Patients with MUO have a poor overall prognosis with the median life expectancy of less than 12 months.1,2 MUO is a feature of advanced cancer and progressive bilateral obstruction leads to irreversible deterioration of renal function. The development of MUO may also preclude chemotherapy and other cancer therapies.

A multidisciplinary approach in the management of patients with MUO is required, as treatment selection is dependent on the prognosis of the patient, and the patient’s performance status combined with available cancer treatment options. Although some MUO can be treated with a retrograde approach, many patients require an antegrade approach by an interventional radiologist. MUO is commonly treated with PCN or with polymeric JJ stents—however, there are other management options available.

Permanent PCN may be required when there is extensive tumour infiltration in the bladder or when the ureteric obstruction cannot be crossed. PCN drainage is a relative contraindication for chemotherapy, requires regular exchanges, and is an undesirable outcome for most patients. Frequent tube dislodgement can occur with PCN, even when using larger-diameter nephrostomy tubes, placing the nephrostomy in a tunnel, or attempting to secure the tube with sutures and dedicated drain-fixation devices. The loop or circle nephrostomy is an alternative in such patients, using a double calyceal puncture. The loop nephrostomy has greater security with less chance of accidental displacement and requires less frequent routine tube changes than standard PCN.3,4

If the bladder still functions, extra-anatomical stenting can be considered through a subcutaneous tunnel and suprapubic access. Extra-anatomic stenting was first described in the 1990s but is seldom offered in PCN-dependent patients with MUO.5 A dedicated device, such as the Paterson-Forrester subcutaneous urinary diversion stent (Cook Medical; 8.5Fr, 65cm) can be placed and exchanged at three monthly intervals under local anaesthetic.

While it is difficult to draw too many conclusions from a limited number of studies, the self-expanding, covered ureteric stents do appear to be more effective in treating MUO, and with better long-term outcomes, compared with JJ stents.

JJ stenting with 6–8Fr polyurethane devices fail to relieve MUO at three months in up to 51% of patients and require regular routine exchange via the retrograde route at three-to-six-month intervals. Stent primary patency is between 40% and 60% at one year.6 An alternative to a polyurethane JJ stent is the Resonance stent (Cook Medical), which is a metal JJ stent made from a cobalt-chromium-nickel-molybdenum alloy and has a maximum indwell time of 12 months before exchange is required. The Resonance has improved primary patency to polymeric stents in some studies with >90% patency at one year, owing to less risk of extrinsic compression and encrustation. In a systemic review, the reported migration is low, at 1%—however, stent obstruction at 17% was seen and patients are prone to the same symptoms of bladder irritation seen with JJ stents.7

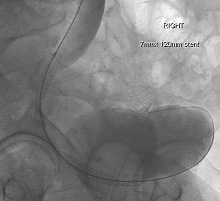

Dedicated covered, self-expanding ureteric stents have become available, which can be inserted either retrogradely or antegradely, and offer alternatives to JJ stents requiring fewer exchanges. Devices currently available include Uventa (Taewoong Medical), which is a double-layered, coated, self-expandable metallic mesh stent. The Allium (Allium Medical Solutions) is a fully covered, self-expanding nitinol stent. The entire stent is covered with a biocompatible, biostable polymer, making it a nonpermeable tube, to prevent tissue ingrowth and early encrustation stent. The Hilzo stent (BCM) has a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) cover in spiral configuration—intended to help prevent stent migration. It is designed with soft and smooth ends to minimise hyperplasia.

All of these devices have a delivery size that is suitable for antegrade insertion—10Fr or less—and when deployed the diameter ranges from 7–10mm. The stents can be overlapped at points of tight narrowing, or in very long stricture, and offer focal distension of the diseased portion of ureter and require less frequent reintervention than JJ stents. Removal and replacement of these devices requires endoscopic intervention with graspers to either unwind or collapse the device.

While it is difficult to draw too many conclusions from a limited number of studies, the self-expanding, covered ureteric stents do appear to be more effective in treating MUO, and with better long-term outcomes, compared with JJ stents. Complications seen include occlusion from hyperplasia, encrustation, migration and fistulation. The cost of the devices is offset by the reduced need for reintervention as compared with JJ stents.7–10

In conclusion, there are more options for treating patients with MUO other than PCN and JJ stents. Avoiding permanent PCN is advantageous to the patient, and significantly reduces readmission for either exchanges or managing the arising complications. Interventional radiologists should consider alternatives such as extra-anatomical stents and self-expanding covered stents when dealing with MUO.

References:

- Izumi K, Mizokami A, Maeda Y et al. Current Outcome of Patients With Ureteral Stents for the Management of Malignant Ureteral Obstruction. Journal of Urology. 2011; 185(2): 556–61. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.102

- Lienert A, Ing A, Mark S. Prognostic factors in malignant ureteric obstruction. BJU International. 2009; 104(7): 938–41. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08492.x

- Noureldin Y A, Diab C, Valenti D et al. Circle nephrostomy tube revisited. CUAJ. 2016; 10(7–8): 223. doi:10.5489/cuaj.3596

- Alma E, Ercil H, Vuruskan E et al. Long-term follow-up results and complications in cancer patients with persistent nephrostomy due to malignant ureteral obstruction. Support Care Cancer. 2020; 28(11): 5581–8. doi:10.1007/s00520-020-05662-z

- Paterson P J, Forrester A. Extra-Anatomic Urinary Diversion. Journal of Endourology. 1997; 11(6): 411–2. doi:10.1089/end.1997.11.411

- Tabib C, Nethala D, Kozel Z et al. Management and treatment options when facing malignant ureteral obstruction. Int J Urol. 2020; 27(7): 591–8. doi:10.1111/iju.14235

- Khoo C C, Abboudi H, Cartwright R et al. Metallic Ureteric Stents in Malignant Ureteric Obstruction: A Systematic Review. Urology. 2018; 118(April 2017): 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2018.01.019

- Kim M, Hong B, Park H K. Long-Term Outcomes of Double-Layered Polytetrafluoroethylene Membrane-Covered Self-Expandable Segmental Metallic Stents (Uventa) in Patients with Chronic Ureteral Obstructions: Is It Really Safe? Journal of Endourology. 2016; 30(12): 1339–46. doi:10.1089/end.2016.0462

- Moskovitz B, Halachmi S, Nativ O. A New Self-Expanding, Large-Caliber Ureteral Stent: Results of a Multicenter Experience. Journal of Endourology. 2012; 26(11): 1523–7. doi:10.1089/end.2012.0279

- Chen Y, Liu C, Zhang Z et al. Malignant ureteral obstruction: experience and comparative analysis of metallic versus ordinary polymer ureteral stents. World J Surg Onc. 2019; 17(1): 74. doi:10.1186/s12957-019-1608-6

Conrad von Stempel is a consultant interventional radiologist at the University College London (UCL) Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK.

Tim Fotheringham is a consultant interventional radiologist at Barts Health NHS Trust in London, UK.

The authors declared no relevant disclosures pertaining to this article.