In 2010, the UK Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) with the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) published a report focused on how to improve paediatric interventional radiology (PIR) services. In June 2023, an updated report was published, this time by the RCR on its own. The purpose of the report is to “identify how PIR services can be expanded and improved” and “suggest solutions” that can be enacted by commissioners, healthcare leaders and hospitals. The conclusion of the 2023 report states that “the 2010 report recognised the value and importance of PIR to the National Health Service (NHS) and made recommendations to grow and support PIR but has not driven change”. In light of this, what do the updated recommendations suggest is needed to drive change successfully this time round?

In 2010, the UK Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) with the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) published a report focused on how to improve paediatric interventional radiology (PIR) services. In June 2023, an updated report was published, this time by the RCR on its own. The purpose of the report is to “identify how PIR services can be expanded and improved” and “suggest solutions” that can be enacted by commissioners, healthcare leaders and hospitals. The conclusion of the 2023 report states that “the 2010 report recognised the value and importance of PIR to the National Health Service (NHS) and made recommendations to grow and support PIR but has not driven change”. In light of this, what do the updated recommendations suggest is needed to drive change successfully this time round?

The introduction to the report seeks to clarify that “PIR is more than just IR in children, and requires specific skills, staff and infrastructure to be done right”. In spite of this, according to the latest RCR workforce census, the UK has 743 consultant interventional radiologists, but less than 20 of those are formal PIR posts. The report goes on to state how the majority of these posts are in London, meaning children and families across most of the UK do not have easy access to PIR services. The RCR’s goal in providing an update to the joint report is to finally “bring PIR service provision into the 21st century”.

PIR in the UK in 2023

The main body of the report begins by listing the advantages to making PIR services fit for purpose, which will bring about faster recovery times through less invasive procedures, and therefore the use of fewer inpatient beds and other resources, as well as a more manageable experience for the patient and their family. The report further informs readers that there is, roughly, only one paediatric interventional radiologist per million children in the UK, to the USA’s one per 342,000 children. Moreover, it states, there is roughly one adult interventional radiologist per 74,000 adults in the UK, yet even this is jeopardised by the “[worrying]” shortage of radiologists generally.

The report also outlines how PIR services are currently delivered, and that a variety of models are used. In a small number of hospitals, the entire PIR service is delivered by paediatric interventional radiologists. In others, some procedures are carried out by adult interventional radiologists, some by paediatric diagnostic radiologists, and others by paediatric interventional radiologists. There are further centres where PIR services are either carried outby adult interventional radiologists, or commissioned to a paediatric specialist at another centre. Beyond this, there are centres where there is no provision in the wider region beyond an adult IR, which can take care of some procedures, but not all.

Acknowledging that some progress has been made

Although the report laments that the 2010 RCR/RCPCH document “has not driven change”, it acknowledges that the latter may have had a hand in bringing about certain recent advances that the RCR “welcome[s]”. These include a new IR training post at Birmingham Children’s Hospital (Birmingham, UK),the second national PIR training post in the UK, and the recent integration of PIR into the adult IR training programme at Guy’s and St Thomas’ and the Evelina London Children’s Hospitals (London, UK). Recently, additional PIR posts have been created at Leeds Children’s Hospital(Leeds, UK), Alder Hey Children’s Hospital (Liverpool, UK), and The Royal Hospital for Children (Glasgow, UK).Beyond this, the RCR has collaborated with the British Society of Interventional Radiology (BSIR)’s PIR special interest group on “the development of a rolling PIR cross-skilling programme, aimed at adult IRs, paediatric diagnostic radiologists, surgeons and anaesthetists”. Nevertheless, the report proceeds to question whether PIR can become centrally funded “so organisations do not view it as an unfeasible financial burden”, which is a current barrier to these positive steps being more widespread.

Solutions set out in the report

In terms of recommended action from various colleges and governmental bodies, the 2023 report echoes much of that which was stipulated 13years prior. Firstly, to address the shortfall in numbers of PIR consultants, the report advocates for doubling the PIR consultant posts available every five years, so that there are 96 in the UK by 2038. Linked to this, cross-skilling, such as has been discussed in collaboration with BSIR, is also key, the RCR believes, as there are insufficient numbers of doctors across radiology and IR, among other specialties, which can impact existing PIR care offered under the various models enumerated above. Adult IR, paediatric surgeons, anaesthetists, radiographers, and nurses could be trained in certain areas of PIR care provision to help compensate for inadequate numbers of PIR service-providing consultants.

The report further recommends that national training bodies such as Health Education England could provide funding for PIR trainee posts, open to final-year(ST6) trainees in IR or paediatric radiology. There is also a need “to consider how to better integrate PIR into existing training curricula” to address the problem of the “relative invisibility” of PIR to medical students and junior doctors. Regarding how to deliver a PIR service, the report emphasises the need for a “clear PIR service delivery policy in all hospitals that offer care to children”. It adds that “unambiguous arrangements must be in place for the early referral of children requiring PIR care that cannot be provided locally in a timely manner”. In order to achieve this, PIR must be included in treatment algorithms, local service models and referral pathways, in cooperation with other specialties such as anaesthesia and paediatric surgery.

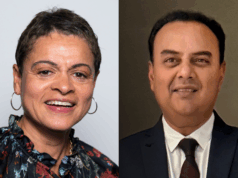

Speaking to Interventional News, report author and PIR consultant at Great Ormond Street Hospital (London, UK), Alex Barnacle, gave her take on which recommendations will be the easiest to achieve. She believes that PIR in the UK is most likely to see an increase soon in the number of PIR practitioners through cross-skilling of healthcare professionals, and training capacity in PIR, as well as some refinements in how data is collected. On the flip side, substantially increasing PIR consultant post numbers poses the greatest challenge.

Asked to comment on the issues outlined in the report, president of the RCR, Katharine Halliday said: “For some of our sickest children, PIR can be a lifeline, providing minimally invasive treatment and reducing lengthy hospital visits. But too few children, whose lives could be improved through these life-changing procedures, do not have access. We are urging the [UK]Government and trusts to take note: this is highly effective, cost-saving care that desperately needs to be resourced.”