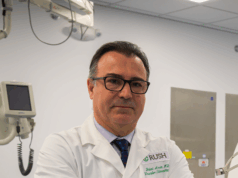

“For me, it was essentially love at first sight,” confessed Gary Siskin (Albany Medical Center, Albany, USA), stating his enthusiasm for liquid embolics—an enthusiasm that is shared by an increasing number of interventionists year on year, he says. As with many emerging technologies, however, benefit, risk and research must be considered before widespread adoption. Here, Siskin and other users speak on the current “fascination” with liquid embolic agents, their future, and the concerns that remain.

“For me, it was essentially love at first sight,” confessed Gary Siskin (Albany Medical Center, Albany, USA), stating his enthusiasm for liquid embolics—an enthusiasm that is shared by an increasing number of interventionists year on year, he says. As with many emerging technologies, however, benefit, risk and research must be considered before widespread adoption. Here, Siskin and other users speak on the current “fascination” with liquid embolic agents, their future, and the concerns that remain.

For Siskin, the incorporation of liquid embolics into his practice began with glue, “the earliest embolic agent” that was available to him and his team. “However, it’s hard to argue the effectiveness of glue,” he stated, due to the “artistry” of diluting glue to ensure successful deployment. As newer embolic agents emerged, the “idea of diluting the product and tailoring it to the indication that you’re using it for has kind of gone away,” said Siskin, leaving space for premade products.

“I think we’re approaching an ease-of-use era, which is going to allow for wider adoption and adaptation of liquid embolics,” he continued. This, he believes, will provide several benefits to interventionists, including reaching hard-to-access vessels, improved packing density and cost-effectiveness.

Enabling him to reach the previously unreachable, Siskin told Interventional News that he frequently uses liquid embolic agents to treat peripheral haemorrhage, vascular malformations, and endoleaks, while having recently expanded to some venous indications. However, “we always need to be comfortable with where the liquid might travel”, he added, noting that this factor plays a large part in identifying a “good” or a “bad” case for the use of a liquid embolic.

“For example, we do bronchial embolization. It might be nice to use a liquid, but there’s a risk of embolizing the spinal cord and sometimes this is not easy to see, so we don’t take the chance,” Siskin said. “I also don’t necessarily think we should be [using liquid embolic agents] in fibroids or knee arthritis—people are starting to use them in prostate embolization, but I think we have a way to go before we can routinely recommend that.”

Siskin described that the “most valuable” quality of liquid embolics are their superior packing density, which he believes rivals coils in both level of occlusion and efficiency. He explained that it is often challenging to fill a vessel with coils, despite only needing to fill a third of the vessel lumen. “It’s difficult to conceptualise that you aren’t filling as much of the vessel as you think,” but with a liquid embolic “if done the right way, it can fill close to 100% of the vessel, maximising packing density in a way that other products can’t ever hope to achieve,” Siskin stated.

“Generally, the teaching that we give people for liquids is to inject them very slowly, especially agents like LAVA [Sirtex] or Onyx [Medtronic]. Even injecting them as slow as you need to, it still results in an occlusion that takes less time than putting in multiple coils or other embolics. I have found that using liquids is a very efficient way to embolize blood vessels,” said Siskin.

Ascribing improved efficiency to enhanced cost-effectiveness, Siskin stated that theirs has become a “liquid-first” practice. Although liquid embolic agents “look cost prohibitive at first glance”, Siskin revealed that a small amount of product is needed to embolize the average vessel, which initiated a “wholesale change” in his practice.

Siskin added: “The reality is that all of the products that we use are getting progressively more expensive. If you’re using, let’s say, pushable coils and first-generation detachable coils, you’re probably not going to be able to make an economic case for liquids. But, if you are using the next endovascular coils or packing coils, you will find that these are very cost-effective and will make a lot of sense for your practice.”

Several studies have recently provided data on liquid embolic agents, including data from the LAVA (Sirtex) trial which found ethylene vinyl alcohol to be safe and effective for peripheral arterial haemorrhage. For Siskin, gaining these insights through clinical trials is “critical”, especially for the peripheral use of liquid embolic agents, so that “appropriate training can finally be given to interventional radiologists”.

Siskin highlighted that enthusiasm for liquid embolic agents is deserved, but interventionists should take adoption “slow”. In the near future, he hopes that ongoing trials will bear out the safety and efficacy of deeper penetrating embolic agents which he believes will have “big potential” for IR.

For now, he asserted that interventionists should aim to understand when is best to use liquid embolic agents: “You’re going to want to look at risk—risk of distal or non-target embolization. Understand the flow in your target vessel. Look at vessel size. Understand the volume of embolism that we reach.”

“We can play two truths and a lie here and say: interventional radiology [IR] is dependent on technology; there will always be new technology that can be easily taken up by interventional radiologists; and IR will always want these technologies. The lie is that it’s easy. Interventional radiologists are largely always interested in learning something new, but I think it’s concern that may hold people back,” said Siskin. “It’s just a question of the interest in bringing something new into your practice and then getting the education and the experience that gives you the confidence to use it correctly.”