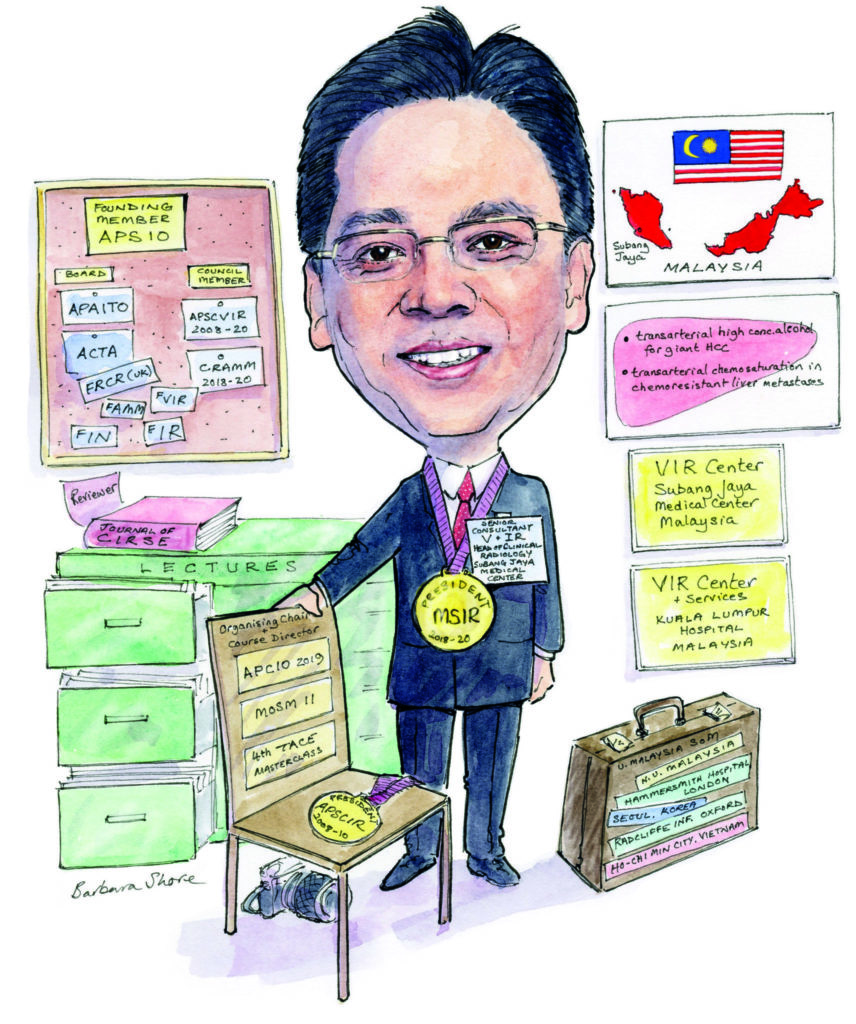

“Deep in my heart, I knew interventional radiology (IR) had a tremendous future,” Alex Tang tells Interventional News. Looking back at his career, Tang talks of setting up IR services in his native Malaysia, and, as the convenor of the Asia-Pacific Congress of Interventional Oncology (APCIO), details the myriad opportunities and challenges interventional radiologists in the Asia-Pacific region face.

“Deep in my heart, I knew interventional radiology (IR) had a tremendous future,” Alex Tang tells Interventional News. Looking back at his career, Tang talks of setting up IR services in his native Malaysia, and, as the convenor of the Asia-Pacific Congress of Interventional Oncology (APCIO), details the myriad opportunities and challenges interventional radiologists in the Asia-Pacific region face.

What first drew you to interventional radiology?

I joined as a radiology trainee at the National University of Malaysia in 1991. This was an unexpected opportunity: a nurse happened to drop the application for radiology training on to my desk during the peak of the outpatient rush. The chances of enrolling in radiology training 29 years ago were as slim as winning the lottery. I was mesmerised by my radiology counterparts, who were able to biopsy the liver percutaneously in a trauma case, in one instance saving a patient with a massive post-biopsy bleed—this was done by my senior using the frightening Vim-Silverman needle. I then obtained a place on a postgraduate training course to eventually become a specialist; the places were full, but the phrase “I want to do interventional radiology” during my interview secured me the training post. Back then, I was not yet aware of how wide-reaching and interesting the field of IR was.

Have you had important mentors throughout your career? What have they taught you?

My training in IR started in the Hammersmith Hospital, The Royal Postgraduate School University of London, UK, under the guidance of Ann Hemingway and James Jackson, from 1997 to 1998. During my fellowship training, I was also seconded to the Guy’s Hospital, London, UK, where I worked under Andreas Adam. Ann Hemingway created the fellowship opportunity for me despite working around a very busy schedule. James Jackson taught me a complex, state-of-art techniques in embolization. Andreas Adam completed my training in the various non-vascular interventions. In addition, Richard Edwards and John Moss were very important mentors to me, because they exposed me so much to various endovascular revascularisation techniques in the Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow, Scotland. I have obtained strong technical skills from all of these mentors. These hands-on training opportunities shaped me to become an all-rounder within IR by the time I returned to Malaysia to start the IR services in my home country. To those who have shaped me to be who I am today, I sincerely thank and appreciate you from the bottom of my heart.

As the convener of APCIO, why did you feel the need for a meeting in the Asia-Pacific region?

Modern oncology is among the fastest-growing fields in medicine. Interventional Oncology (IO) being the fourth pillar of cancer care, it is one of the most rapidly evolving sub-specialties. The practice of IO in the Asia-Pacific region is extremely variable; we have to take into consideration the varying standards of care, technologies, and availability of services, as well as the diverse geographies, ethnicities, socio-economic backgrounds and skills in each and every country.

With the theme “Interventional Therapy in Modern Oncology: Technological Integration Beyond Boundaries”, APCIO 2019 is multidisciplinary and multinational. The meeting aims to establish a regular platform from which to discuss ways of continually improving medical expertise, while also ensuring the delivery of best ethical practices in oncological patient care. APCIO 2019 enrols almost every country in the Asia-Pacific region, with the primary aim of developing an even greater interest in the next generation of interventional radiologists.

APCIO 2019 also wishes to strengthen intersocietal collaborations, with associations such as the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), the Asia Pacific Society of Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology (APSCVIR), the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE), the Society of Interventional Oncology (SIO), the Asia Pacific Primary Liver Cancer Expert group (APPLE), the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL), the local oncology society and many more.

How has the APCIO changed over the last six meetings?

APCIO was first established in 2010 in Beijing, China, by the Asia Pacific Society of Interventional Oncology (APSIO). It is a biennial meeting of interventional radiologists from the Asia-Pacific countries. The last five meetings were held in Beijing, China, 2010; Hangzhou, China, 2011; Guangzhou, China, 2013; Miyayaki, Japan, 2015; and New Delhi, India, 2017. The sixth meeting will be held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2–5 October 2019. With the premise of providing a multidisciplinary approach and fostering intersociety collaborations, APCIO 2019 is establishing a collaborative platform in interventional oncology in the region. We see positive steps in having non-interventional radiologists coming forward to collaborate with and to support the meeting. This is very encouraging and favourable development. With IO being the fourth pillar of modern oncology, it is vital that we work with the other three pillars to offer more holistic and multidisciplinary care in the best interest of cancer patients. Moving forward, future APCIO meetings will see a greater symbiosis with our clinical counterparts in surgical oncology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, immunology, stem cell medicine, modern pathology, palliative care and various support groups in the modern oncology field.

What are the challenges and triumphs of interventional radiology specific to the Asia-Pacific region?

Asia Pacific countries are geographically, ethnically and financially diverse. The standard of care in medicine, especially in the field of interventional radiology, varies throughout the region. The disease spectra, presentations, and incidences also vary regionally and are different from in western countries.

Whilst numerous procedures are performed to the best achievable local standards, they frequently have suboptimal outcomes, especially in the economically under-privileged countries. Procedures are also performed in diverse ways, and optimal endpoints for the best result may not have been reached. One example is conventional transarterial chemoembolization (cTACE) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): the technical approach, patient selection, and outcomes are extremely variable. Skill level, equipment availability, and financial constraints—notably a lack of national healthcare financing—present daily challenges.

There is a huge need for streamlining the standard of care, procedural techniques, and skills, regional availability of necessary equipment for procedures—from the very basic to the most advanced—and the training of young interventional radiologists across the region. This should be our priority. APCIO wishes to do this by gathering everyone under one roof on a regular basis, with the hope of strengthening the regional IO/IR fraternity. To this end, 80 young investigator awards are given out at the meeting. These are strongly supported by the industry, with the hope of bringing delegates from financially restricted countries, as well as providing individual benefit to the recipients. Two US$3,000 training scholarships are also provided.

What is the most exciting research coming from the Asia-Pacific region in interventional oncology, in your opinion?

The paper from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, on the “Ablative chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective phase I case-control comparison with conventional chemoembolization”, by Simon Yu et al. It was published in Radiology in April 2018. The management of giant HCC, an endemic disease in the Asia-Pacific region, has been a great challenge to all of us. Treating and completely controling a giant HCC in a non-resectable candidate with cTACE or DEB TACE is frequently futile. The use of transarterial ethanol injection (TEE) in the embolization of liver cancer was first attempted in the 1970s in Japan. This treatment technique was abandoned because of multiple technical failures.

Technical improvisation and improvements in safety have optimised this procedure, and Yu et al published a paper in the Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology in March 2009 detailing their positive experience of TEE. Ever since, TEE has been gaining momentum, with more interventional radiologists using this new treatment modality in the management of intermediate-stage HCC.

Yu has attempted to further advance the treatment for HCC by adding an element of chemotherapy (cisplatin) into the formulation of TEE, to develop what he calls ablative chemoembolization (ACE). His study published in Radiology has proved the safety of this new and highly effective treatment. A 100% complete remission rate using the ablative chemoembolization protocol has been reported; a very encouraging development.

In my personal experience, TEE/ACE offer numerous advantages and has fewer side effects. It is highly efficacious in controlling the tumour, especially if it is injected super selectively into the tumour. Ethanol has the property of instigating immediate cellular coagulation; hence, it achieves an immediate tumour necrosis, especially if a concentration of more than 66% is used during the procedure.

As president of the MYSIR, what are your goals for society?

The Malaysian Society of Interventional Radiology (MYSIR) is a young society, established in 2013. Our main goals are: to establish a more streamlined standard of care in IR/IO, to train more young blood, to promote IR services locally, and to enhance our presence in the daily clinical workflow. MYSIR is working collaboratively with multiple disciplines to gain greater clinical acceptance of the newer IR technologies and treatment modalities. We are organising more multidisciplinary team meetings, among them the Multidisciplinary Oncology Symposium Malaysia (MOSM) and APCIO 2019.

MYSIR is an organisational member of the Asia Pacific Society of Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology (APSCVIR), and we are looking forward to having a greater presence both regionally and internationally, and to establishing a more cohesive collaboration with larger societies, such as SIR, CIRSE, Society of Interventional Oncology (SIO), ACTA, APPLE and APASL, to promote IR services and to conduct training workshops for local IRs and trainees.

What is the biggest challenge for IR at the moment?

The public awareness of the availability of IR treatment techniques is still low, especially in some Asia-Pacific countries. Similarly, in the medical fraternity, many doctors are unaware of the availability of the state-of-the-art options IR offers in the management of diseases. Clinical acceptance of the new IR techniques is also a big challenge for us, as many of the clinicians prefer to opt for more conventional means.

Evidence-based medicine and clinical outcomes remain the most important determinants of our daily practice. High-quality research and clinical evidence in IO and IR treatment techniques are still lacking, and they are needed to justify our clinical presence and in offering the best medicine for the best interests of our patients.

What do you anticipate being the most practice-changing technology in IR over the next 10 years?

Artificial intelligence (AI), especially machine learning (ML), is expected to play a primary role in the future of IR. This is especially true for minimally invasive tumour therapies performed by interventional oncologists. The overwhelming amount of disparate clinical, laboratory and imaging data derived from clinical research is beyond anyone’s ability to digest, and thus cannot be systematically applied in the everyday clinical setting. This results in institutional and individual variabilities in multidisciplinary decision-making involved in daily patient management. The growing need for more patient-centred and individualised care necessitates a more systematic and unbiased approach for determining case stratification, treatment protocols, outcome predictions and, most importantly, avoiding those treatments that are not (or less) effective. AI solutions can use ML algorithms in precise planning and may help make sense of the potentially nonsensical. This will cause a paradigm shift for interventional oncologists, improving clinical outcomes to the extent that it will be the mainstay of IR practice.