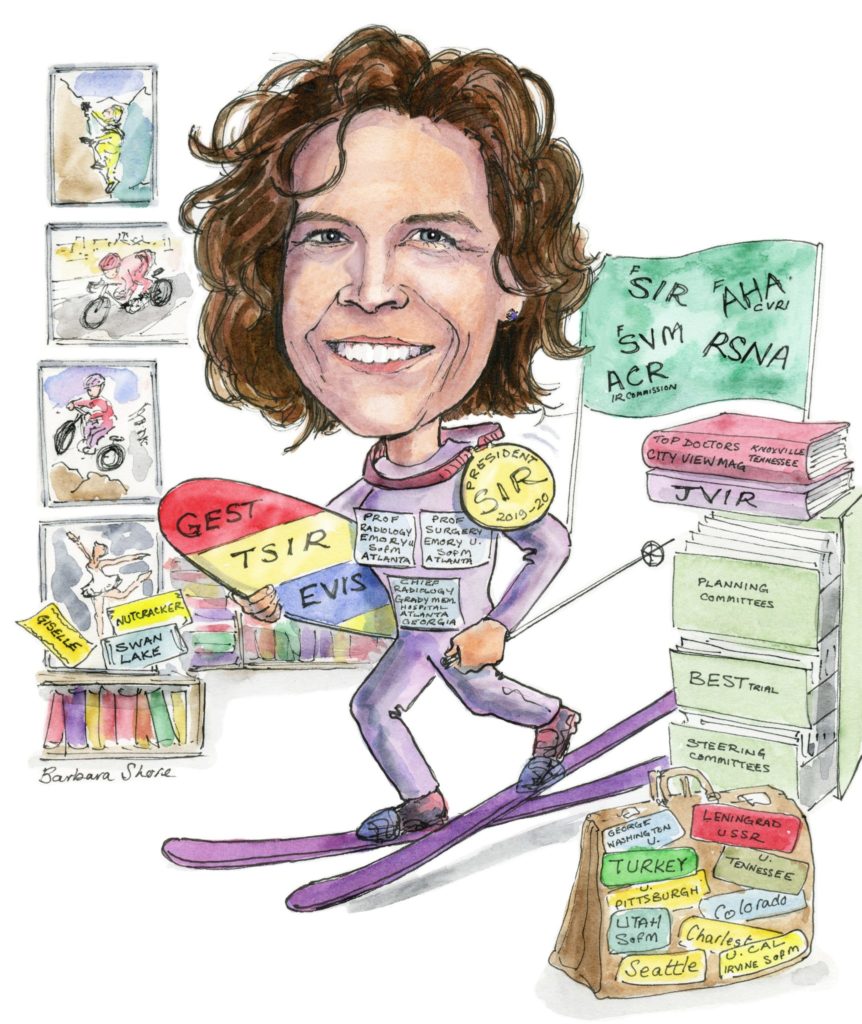

After coming across interventional radiology in a “fortunate accident”, the 2019–2020 Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) president Laura Findeiss talks to Interventional News about her career, the future of the discipline, and the importance of working across disciplines to foster the creative thinking necessary in difficult cases.

After coming across interventional radiology in a “fortunate accident”, the 2019–2020 Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) president Laura Findeiss talks to Interventional News about her career, the future of the discipline, and the importance of working across disciplines to foster the creative thinking necessary in difficult cases.

You started your residency in surgery, but then changed to interventional radiology (IR). Why?

Lots of factors. For one thing, I found myself burned out. That was before work hour restrictions, and there was a different culture in surgical training programmes. When I lost my originally deep compassion for patients, I realised that I could not do it anymore. I loved operating, but even this lost its lustre. After I left my residency, I spent a year working in rural hospital emergency departments (really, emergency rooms) in Tennessee, and this was a great experience for me, learning true clinical independence and gaining an understanding of what rural medicine is really like—how isolated some of these places are even now. Ultimately, choosing a radiology residency was a process of exclusion and was not particularly deliberate. I enjoyed the imaging very much, but was like a fish out of water without the hands-on patient care. When I “discovered” IR, it really was a perfect combination of the beauty of imaging and the ability to care for patients in a creative and technically challenging way. When you have cared for lots of patients recovering from surgery and see the difference our techniques make, you see how truly impactful it is.

Have you had important mentors throughout your career? What have they taught you?

Yes! So many. The chief of IR at my residency programme, Ellen Hauptmann, was so committed to doing the right thing for patients, and she was such a role model for me. Her compassion, knowledge base, imaging skills and true technical ability were part of what really attracted me to the specialty. I learned about what it means to be a great colleague from her, as she was so collaborative with all the referring specialties. The chief of IR in my fellowship, Torre Andrews, was great at talking to patients at their level, and that was great to observe. He became a true sponsor, as he was the one who got me involved on committees in the SIR, and it was that early engagement that got me energised and networked in the society. He was one of a core group of SIR members pushing the clinical practice paradigm early on, and his passion about this issue reinforced my own. Finally, Scott Goodwin, who gave me a great opportunity when he hired me at the University of California at Irvine as section chief, was a great mentor in that he let me execute my vision with guidance and trust. He really stood back and supported me in the background while I ran the section in the direction our team wanted to go, and that was just a fantastic leadership experience that gave me the confidence to move on to other roles. It also taught me about leading by supporting others.

In several of your workplaces, access to IR services has been limited. What are some common barriers to access, and how can these be overcome?

This topic is really important to me. I think the biggest barrier to access in many places is the lack of an IR in a community or hospital. Recent literature looking at the distribution of providers of image-guided interventions throughout the USA validates this perspective; the availability in communities is dismal. This applies, unsurprisingly, to extremely rural locations, but I think the big shock is how even suburban and not-so-remote areas suffer from this lack of availability.

I see this as an amazing opportunity for our specialty. We have a generation of IRs emerging from training now, more independent and clinically-minded. From my point of view, so many of the communities that would benefit from the presence of an IR are great places to live and grow diverse practices. Talking to young IRs who have had an opportunity to take advantage of these availability gaps, I am amazed at the high-quality practices they have built, and how rewarding this process has been for them.

One barrier that has been raised with regard to growing an IR practice in communities has been the “exclusive contracts” issue in the USA, whereby IRs may be ineligible to get hospital privileges if they are not affiliated with the hospital’s radiology group, but may find that they are unable to practice the way they wish to, in a more clinical fashion, within a radiology group. We have members advocating on both sides. SIR is actively working to find common ground on this topic through collaboration with the ACR’s IR Commission and the General, Small, Emergency, and Rural (GSER) groups Commission, as these issues are a mutual concern.

As a self-described “systems operations geek”, how does thinking systemically aid you in your work?

In my current role as chief of Service for Radiology at Grady Memorial Hospital, a large public safety net hospital in Atlanta, I am working to improve our systems and operations to provide better efficiencies in care to create more access without increasing costs. We are relatively under-resourced due to our mission of caring for a largely self-pay, county-funded, and Medicaid-funded population. On top of emphasising process improvement methodology, I am focusing on change management principles, since all of this requires significant cultural reorientation and generation of buy in on multiple levels. I love the challenge of navigating all of this with the promise of better access to higher quality care for our patients. Before this role, using the same kind of systems thinking was really important for some of the structural changes I have participated in in other places: leading institutional change around procedural sedation standards, creating best practices in the IR area, negotiating a hospital contract focused on aligning incentives to achieve common goals. I think backing up and establishing the target state and thinking systematically about how to achieve the goals is always a best practice.

As the president-elect of the SIR, what are your aims for the society over the next 12 months?

We have already touched on a major theme: access to care. I truly believe that there are significant disparities in patient outcomes related to lack of access to IR. I also think that our burgeoning clinical IR workforce is a great match to this challenge. If we can navigate, through our collaborative work with the ACR, the current challenges in creating avenues for clinical IR practices within or alongside radiology practices, we can create a win-win(-win) for radiology practices, IRs, and communities.

Another topic that is very important to me is that of promoting and supporting diversity in our specialty. The SIR has a goal of creating an inclusive environment. I hope to make progress on this front over the next year, particularly with respect to establishing venues for engagement and solidifying the platform from which specific, member-driven efforts can launch. The SIR should be a place where all IRs can find a sense of belonging.

You are an advocate for multispecialty collaboration within healthcare. How can this be improved?

I firmly believe patient outcomes are better, and care is more efficient, when there is open and respectful communication between different specialties. In so many places we find ourselves in conflict with other specialists over areas of mutual expertise, configured as turf battles or even just ego battles, and patients are the losers. Physicians can easily get distracted from best patient care in these kinds of environments—watching your back instead of watching the patient. It is just another systems thing, in that reducing friction between specialties will help us to use institutional and system resources better and reduce cost, improve efficiencies, and optimise outcomes. Modifying incentives, of which monetary rewards are only a part, can help. To improve collaboration for the benefit of patients will ultimately take strong institutional and systemic leadership focused on reducing the incentives to compete and increasing incentives for collaboration.

Would you describe a particularly memorable case?

One of the most rewarding cases I did was early in my career. I had a patient referred for evaluation for a spontaneous portosystemic shunt. She had presented to our hospital comatose from severe hepatic encephalopathy and she had suffered from medication refractory bipolar disorder and schizophrenia starting early in adolescence. She had been institutionalised for many years, and had reportedly displayed psychotic behaviour. There is a lot in the veterinary literature about congenital portosystemic shunts in dogs, who demonstrate bizarre behaviours that can resolve with surgical occlusion of the shunts. We wondered if this was in play. Then we learned that the antipsychotic and other medications she was on are dependent on hepatic metabolism—the metabolites are the active agents. After a lot of multidisciplinary discussion, I ultimately occluded her shunt and psychiatry modified her medications. She ended up being discharged home to self-care after a few months with the support of her adult daughter. In follow-up, she thanked me for giving her a relationship with her daughter. This case is a reminder to think outside the box, something I think IRs are really good at.

What is the biggest challenge in IR at the moment?

We are in a major transition with the training pathway, and this is bringing learners with different perspectives and expectations into the specialty. I think this will be good for patients and the specialty if they can execute on the promise of a new kind of practice model. It is going to be disruptive, though, to radiology, and I am glad we are starting to talk about this at the SIR-ACR level.As a society, our imperative is to help get our members the tools they will need to navigate the changing landscape through productive negotiations with radiology practices, hospitals, payors, health systems, or whatever entities they need to work with to build the practices that make the most sense in their local environments. One big challenge is how different local environments are from each other in our health system, so the approach cannot be one size fits all.

Outside of your own research, what has been the most interesting paper that you have seen in the last 12 months?

Rosenkrantz et al, “Generalist versus Subspecialist Workforce Characteristics of Invasive Procedures Performed by Radiologists”, in Radiology online. An incredible take home point from the article was that only 347 counties throughout the USA have access to an IR, and only 869 counties have access to a generalist radiologist who performs procedures. This clearly shows that a large part of the country is un- or under-served from the standpoint of IR and we need to look at how to address these access disparities.

What do you anticipate being the most disruptive technology in IR over the next 10 years?

Targeted molecular therapies. In addition to immunotherapy, I see a lot of promise in the theranostic arena, with molecularly-targeted imaging/radiotherapy agents for diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of response to therapy. I can actually see IR playing a big role in the transarterial delivery of these agents to tumors, since intravenous administration is fraught with problems from a dosimetry point of view. These applications are just a one-off from what we already do with SIRT [selective internal radiation therapy]. It is another reason to make sure we maintain our ability to achieve AU status, and the molecular therapy piece is an important reason for IR’s to engage in bench research.

How has the field changed since you started your career?

There is the obvious answer of case mix—early in my career my whole practice was abdominal and then thoracic endografts, renal artery stenting, carotid stenting, and CLI [critical limb ischaemia] intervention. I had to strive to start programmes for chemoembolization, UAE [uterine artery embolization], and TIPS [transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt]. That landscape continues to change and can always be expected to change, since our talent as a specialty is figuring out how to treat disease in different, less invasive, innovative ways, and if we do not see procedures migrating out and new ones migrating in then we are not innovating.

Even more important is the change in the understanding of what it means to practice clinically. Early in my career I was, I think, in great company, but in the minority as far as beating the drum on having to have a dedicated clinic model and practice like any other procedural specialty. It is great to see how this concept has been embraced and is now at the core of our training programmes.

What are your interests outside of medicine?

A lot of individual sports: skiing, snowboarding, road cycling, mountain biking, rock climbing, wake boarding. I started triathlon recently, and have been learning how to telemark. I love to travel, and enjoy ballet and a good book (but these days most of my books are sitting on a shelf staring at me, reminding me they want to be read).