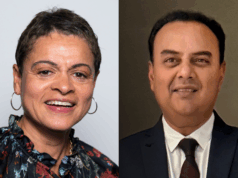

Medical oncologists Filippo Pietrantonio and Marina Chiara (both Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy) have launched a social media campaign called #knowyourstatus to advocate for the “periodical and frequent testing” of SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the virus that causes COVID-19, in healthcare workers treating patients with cancer.

Medical oncologists Filippo Pietrantonio and Marina Chiara (both Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy) have launched a social media campaign called #knowyourstatus to advocate for the “periodical and frequent testing” of SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the virus that causes COVID-19, in healthcare workers treating patients with cancer.

“Our aim is to guarantee separate and ‘clean’ pathways for patients with cancer,” they write in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Oncology. “Even if this objective is failing in front of our very eyes, we will not give up on maintaining the involvement of institutions, patients’ advocacy organisations, and oncologist associations.”

In an opinion piece chronicling the dawning realisation of the severity of the current pandemic in Italy, Pietrantonio and Chiara write: “At this moment, we feel unprotected. Although everyone in the newspapers is praising physicians as heroes, we feel alone, thrown into jeopardy, thrown into an abyss. Our region has left us to fight the cancer battle and the COVID-19 war without true protection, without knowing whether we are infected with the virus. We go to work every day because we love our jobs, and this is the life we have chosen. But we are people, too; we are afraid of getting infected, of going home in the evening, of infecting our children, our parents. […] We live with the absurdity of trying to cure patients of a disease like cancer at the same time potentially being the vehicles for a virus that might kill these very patients.”

They dwell on the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) available to physicians, and the criticise the low level of testing of healthcare workers in northern Italy. “We were terrified after reading the recent reports on undocumented infections as a crucial source of contagion. We were terrified when we thought about models of transmission when applied to our daily lives here at the hospital. Unfortunately, during the past few days, we have been facing the terrific and very real effects of the lack of prevention of intra-hospital infections. In the Lombardy region, the epicentre of the outbreak in Italy, and in many other regions in Italy, asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic health care workers who had contact with patients confirmed to have COVID-19 are not routinely tested unless they develop severe symptoms. Individual protection devices are often lacking and cannot be used for intermediate-risk scenarios. Some of our colleagues have tested positive and are now at home or, even worse, hospitalised in intensive care units. Some of us have already infected entire families, children, grandparents.”

Describing the initial approach to cancer care at the onset of the pandemic in Italy, Pietrantonio and Chiara say that they had to determine the risk-benefit ratio of using intensified treatments and treatment combinations, maintenance strategies, and later-line treatments for each of their patients. These “hard-to-make decisions” were discussed in multidisciplinary team meetings held over video call, and then communicated with patients. “As physicians of a referral centre facing the lockdown of the whole country, we had to decide what to do for some patients with cancer already enrolled in clinical trials, and the patients who faced travel disruptions and the lack of flights from the south of Italy to our hospital in the north, and the fear these patients with cancer had of being infected with COVID-19 while traveling,” they say.

Their piece also captures the emotional toll the COVID-19 pandemic is taking on physicians in Italy. With frequent mention of the “terror”, “loneliness”, “fear”, and “anger”, Pietrantonio and Chiara recount: “We meet colleagues and patients and even laugh about funny stories, but it is clear to all of us that the level of stress and the risk of burnout that health care professionals are facing is alarming.”

They conclude, however, on a hopeful note, emphasising the importance of international unity in the face of a shared global crisis: “In this time of fear and anger, the most important thing is sharing. We have found ourselves united across borders. We have felt the love of so many people for us and for our country. How do we survive, then? With love for our patients, for our professions, and thanks to the sharing that has been created between us.”