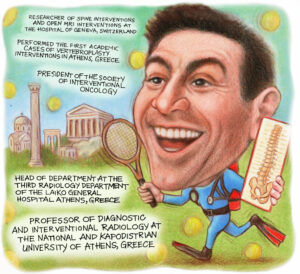

Expanding the limits of interventional radiology (IR), Alexis Kelekis (Athens, Greece) has had many firsts; as the first to perform vertebroplasty cases in Greece and the first international president of the Society of Interventional Oncology (SIO), Kelekis’ career has sought to drive the specialty forward both on the table and through society leadership. In his current roles as professor of diagnostic and interventional radiology and director of the third radiology department at the National and Kapodistrian Univeristy of Athens, Greece, he channels his enthusiasm and expertise to achieving excellence in patient care across interventional oncology (IO), IR, and musculoskeletal intervention. Here, Kelekis discusses his career from its earliest beginnings to present day while pinpointing the landmark developments in IR he has seen along the way.

What was it that drew you to medicine and to IR in particular?

I consider myself both fortunate and humbled to have been born into a medical family, with my grandfather, my uncles and my father practising as radiologists. At one point, my immediate family included no fewer than seven radiologists, each in a different subspecialty of radiology.

From a young age, I was immersed in this world. As a teenager, I would spend school vacations in the radiology department, helping in the lab, carrying, exposing, and printing films by hand, as was standard practice at the time—or archiving cases. Later, when the first digital angiography systems arrived, I began working with image post processing and enhancing. This was an exciting introduction to technology, and I still remember the fascination of working on some of the first computers I had ever seen.

My father, one of the pioneers of IR in Greece, made the radiology department and the interventional suite feel like a second home. Growing up in this environment, choosing radiology—and particularly IR—felt not just natural, but inevitable. I will never forget the sense of awe and responsibility I felt as a young trainee, feeling the warmth of a patient’s blood on my gloves during my first groin puncture using the Seldinger technique. The meticulous process of cleaning, holding, and manoeuvring catheters and wires during those early cases left an indelible impression on me. Even now, that formative experience continues to shape my respect for the craft and my commitment to patient care.

Who have been your mentors throughout your career and what is the best advice they have given you?

I have been privileged throughout my career to have mentors and colleagues who supported me and taught me invaluable lessons, both professional and personal. In the moment, you rarely grasp the full significance of each encounter or experience, but looking back, you begin to appreciate the sequence of events and relationships that shaped you into the person you are.

My training in Switzerland at the University Hospital of Geneva under the guidance of François Terrier, was pivotal in developing my skills in IR, spine, musculoskeletal imaging, and pain management. One morning, as a young resident sipping coffee in front of a vending machine, I met Jean Baptiste Martin. From that day on, he took me under his wing and taught me generously and without reserve.

In the same group, Daniel Ruefenacht and Christoph Becker trusted me to work in the first interventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suite in the early 2000s, where I had the opportunity to practise some of the very first cryoablations and radiofrequency ablations in an MRI environment.

I feel fortunate to have been able to ride the crest of scientific innovation during the early days of bone augmentation procedures, working alongside true pioneers such as Harve Deramond in vertebroplasty and Jacques Theron in disc treatments. Those formative years instilled in me a love for creativity and innovation, and a sense of joy in the work itself.

One of the most enduring lessons came from Kieran Murphy, who taught me always to carry a piece of paper to sketch out ideas— to experiment, to improve procedures and treatments, and above all, to enjoy the process. My mentors and friends led by example and taught me to listen (thank you Sean). I learned from them that the greater the legend, the humbler the person.

Over 25 years, Jean Baptiste and I have worked side by side, always striving to improve procedures—talking, thinking, designing, and performing together—and having an incredible time every step of the way.

Could you outline one of your most memorable cases?

Could you outline one of your most memorable cases?

One of my most memorable cases was among the very first vertebroplasties I performed for bone augmentation, on a bedridden patient in Greece. The fracture and treatment were fairly standard. That evening, when I visited the ward, the patient was pain-free and, after six months confined to bed, was able to stand and walk.

I vividly remember the other patients in the ward rising to their feet, applauding and cheering. To them, it seemed nothing short of a miracle. They had witnessed this man arrive in agony, suffering intensely, carried in on a stretcher. And now, just hours later, he was walking out of the hospital.

It wasn’t the most technically challenging or complex case I ever handled, but it was undeniably the most impactful moment in someone’s life. This is the memory I return to whenever I feel disappointed or discouraged—a reminder of how truly blessed I am to have the ability to change people’s lives.

You have recently taken on the role of president of the SIO. How do you hope to make your mark in this position? What do you hope to achieve?

Being selected by one’s peers from across the globe to serve as their chair is both a tremendous privilege and a profound responsibility. My experience with the society has been an extraordinary journey of learning, guided by a board of exceptional colleagues who have generously shared their wisdom, experience, and patience.

Within SIO, I have rediscovered the creativity and inspiration that fuelled my earliest years in the field. Surrounded by like-minded individuals committed to advancing patient care, we focus on advocating for the benefits of minimally invasive oncology procedures. IO stands today as the fourth pillar of cancer care, and it is our mission to champion it loudly and proudly—for all the patients in the world that deserve the very best.

It is a profound honour to serve as the first international president of SIO, and I am deeply committed to supporting and strengthening the society’s global character. We must foster an environment that promotes standardisation and verification of procedures, ensuring that percutaneous treatments are delivered with the highest quality and reproducibility. My hope is that SIO will continue to provide worldwide leadership and support for IO, advancing care and improving outcomes for patients everywhere.

Looking ahead, my vision is for SIO to be a beacon of innovation, education, and collaboration, uniting clinicians, researchers, and industry partners across all continents to transform cancer care through minimally invasive techniques. Together, we will set new standards, empower practitioners, and most importantly, improve the lives of millions of patients worldwide.

What do you anticipate will be the next big advancement in IO?

I believe that interventional percutaneous procedures for oncology will continue to gain wider acceptance, as we increasingly recognise their synergies with other treatments, together with medical therapy, surgery and radiotherapy. Emerging evidence suggests immunologic reactions associated with the release of molecules following percutaneous treatments, could potentially be harnessed by immunotherapy to create powerful synergistic outcomes and innovative therapies.

Both patients and physicians are becoming more aware of IO solutions and their ability to complement standard therapies, paving the way for more integrated and effective cancer care.

You performed the first academic vertebroplasty cases in Greece. Can you describe your experience?

Introducing a new technique and creating a paradigm shift is always extremely challenging and complex. Peers are, quite understandably, cautious about adopting new procedures—but in my experience, once these techniques are validated, they are quickly and enthusiastically embraced. The journey has been nothing short of a rollercoaster, with multiple layers to navigate—physicians, administrators, insurers, and of course, patients. And yet, I can say without hesitation that it has been worth every effort, and I would do it all over again. We faced significant scepticism along the way, but seeing a once incapacitated patient walking again is truly priceless.

Having played a role in numerous research papers regarding ablation, what do you believe will be the next significant development in ablative therapies?

In recent years, we have been fortunate to witness the ongoing evolution of ablation systems and devices—improving accuracy, reproducibility, and precision. The most recent advances are already transforming our practice, as enhanced planning, guidance, and confirmation tools are increasing our success rates. Integrating these technologies directly into imaging equipment enables better targeting and more effective tumour destruction. Our tools are evolving to provide optimised treatment solutions supported by real-time imaging, and interventional radiologists are now rigorously planning the technique and volumetrically verifying results. This threefold paradigm—planning, executing, and verifying, increasingly supported by artificial intelligence (AI)-driven software—will truly transform the future of ablative therapies.

What have been some of the most important developments in IR over the course of your career so far?

As a child, I grew up in the era of cassette tapes, black and white televisions without remotes, and parents smoking in cars—so you can imagine that I’ve witnessed my share of changes over the years. IR has evolved right alongside this technological revolution, transforming itself completely over the decades.

Some of the most monumental changes have come from the introduction of computerised imaging devices, such as angiographic equipment with subtraction imaging, as well as the development of catheters and wires with memory shapes, and new materials that made microcatheters and guidewires possible.

But the evolution of IR has not been purely technological. At its core, the specialty itself has grown and matured, building robust clinical services and transforming from a niche subspecialty into one of the most sought-after specialties in medicine, attracting some of the brightest and most creative minds.

What does your life look like outside of medicine?

What life outside medicine? No, I’m joking. There absolutely must be a life outside medicine, because one needs to regenerate one’s thoughts and replenish one’s soul. To be able to step outside the confines of one’s professional micro world and see things differently.

For me, life outside medicine is about my wife, my family, friends and pets; it’s about those, who remind me of the world beyond my profession and help me appreciate all that I have and all that I share. It’s about leisurely summer afternoons, lounging on a small boat in a quiet cove of a Greek island, listening to music with loved ones, enjoying the sunset with a great book at hand—praising nature and feeling grateful for living a full and meaningful life.