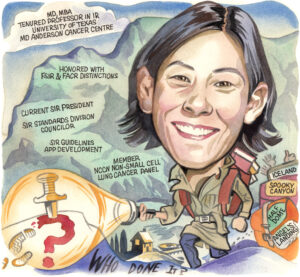

Alda Tam is an interventional radiologist and professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, USA, and is current president for the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR). As an active and prolific researcher, Tam speaks to Interventional News about the trajectory of her career, maintaining her practice alongside her involvement with clinical trials, her development of clinical practice guidelines and more recent app development.

What attracted you to a career in interventional radiology (IR)?

Third year medical school came with the task of having to choose a future career and I had to decide whether I would be more interested in using my hands and operating (surgical specialty) or seeing patients and engaging in cerebral work (medical specialty). With an undergraduate degree in neuroscience and leaning towards surgery, I thought about neurosurgery and signed up for a summer research internship, complete with shadowing in the operating room. During one of the cases, I remember seeing brain tissue in the Yankauer suction and tubing and thought “I don’t know about this…maybe there’s something out there with more finesse?” During my radiology rotation, one of the faculty suggested I check out IR since they knew my affinity for surgery. It only took a few assignments in the IR suite to realise this was it for me; the complexities of surgery with the finesse I desired. That’s how I ended up entering the field.

Who were your mentors?

I completed my radiology residency at the University of Southern California (USC) and had an awesome team of IR mentors: Sue Hanks, Vicki Marx, Michael Katz (all Keck Medicine of USC, Los Angeles, USA), and Donald Harrell (Mammoth Hospital, Mammoth Lakes, USA). I witnessed a high-functioning team delivering top notch care while having fun doing so, and thought that I could see myself in a career like that. During my fellowship at MD Anderson, I continued to find guidance from Marshall Hicks, Michael Wallace, Sanjay Gupta, and Steve McRae (all University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Housten, USA). They gave me my first job, and the rest is history. As my network has grown over time, there are many colleagues, friends, and peers—too many to name—who I continue to rely on for counsel and support. I only hope that I can serve in a similar manner to future interventional radiologists.

What led you to oncology? Was it always your intention to specialise there?

Becoming an interventional oncologist was pure serendipity! My husband is a medical oncologist and the years of training for internal medicine/oncology and radiology were not perfectly aligned. He was matched to Houston first and I joined him there after finishing my final year at USC. But I then finished my fellowship first and started my faculty position at MD Anderson while he was in his last year of training. Then we both ended up staying and we’ve been Houstonians for almost 20 years.

Could you describe a particularly memorable case of yours?

I’ll always remember my first case as a solo operator. I was the second year resident on-call and had been given the go-ahead to start the case by my attending, who was finishing up in the other room. Although it is what most interventional radiologists would consider a bread and butter case—a 65-year-old man in urosepsis, complete with hypotension and tachycardia, from ureteral obstruction related to stone disease, needing a nephrostomy tube—it was definitely an exciting yet nerve racking moment for me because once the patient was prepped and draped, we got word that there had been a hold up in the other room and my attending said, “start if you feel comfortable but if not, you can wait”. In all honesty, I would have preferred to wait, but the patient’s vital signs were not good and getting worse, so I made the decision to act and put in the nephrostomy tube. I will never forget the support of the seasoned radiologist technologist and nurse team who encouraged me and got me through the case. The patient defervesced after the pus in the collecting system was drained, was discharged out of the intensive care unit to a regular floor, and then subsequently home. As I realised what could be done with a needle and wire, this case became one of the moments that cemented my decision to specialise in IR.

What are some of the challenges which face interventional radiologists providing cancer treatment today?

Awareness and access. We continue to face the challenge of physicians and patients being unaware of the value IR can add to oncology care across the spectrum of diagnosis, local treatment, and palliation. That’s why it is key for us to emphasise the importance of IR research and IR-driven clinical trials to obtain the data that will permit the inclusion of our therapies into treatment guidelines. This would ensure that patients can be presented with all the available treatment options. We also have a challenge with patient access to IR. In the USA, approximately 30% of the country’s population do not have access to an interventional radiologist in their state (Ahmad Y et al). When you scale this concept, I suspect that there are many cancer patients globally who could benefit from the treatments that IR has to offer, if only their access to IR care could be improved.

Your largest body of work regards biopsies in oncology clinical trials. How important is biopsy acquisition?

This body of research has led to efforts to standardise biopsy acquisition within the National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Network (ETCTN). The difference between a biopsy for clinical care and a biopsy for research purposes is that oftentimes, a patient enrolled in a clinical trial that requires a research biopsy that may derive no direct benefit. Working at MD Anderson in the mid-2000s, we began to see an increase in the number of clinical trials that were incorporating research biopsies into their trial design and also realised that more tissue was usually needed to meet the goals of a research biopsy. This naturally brought up questions about how to optimise biopsy yield to inform trial endpoints while at the same time protecting patients from undue adverse events. Our collaborative group of medical oncologists, pathologists, and interventional radiologists at MD Anderson have performed research in this area.

In one early study, we examined transparency, meaning how the risks and adverse events associated with biopsies in clinical trials are discussed within informed consent. We reviewed the IR database to identify all therapeutic clinical trials in which image-guided research biopsies were performed from 1 January, 2005, to 1 October, 2010. Among 57 clinical trials, 67% contained at least one mandatory biopsy. Most of the studies failed to convey the risks and benefits of research biopsies in study protocol and informed consent. We also evaluated how often the biopsy results of clinical trials are reported. We searched ClinicalTrials.gov for trials in oncology with completion dates between 1 January, 2000, and 1 January, 2015, with endpoint category terms including biopsy, biopsies, or tissue.

Among 301 trials, only 50.8% reported any biopsy-related results. In a similar analysis of 866 research biopsies performed across 46 clinical trials, 61% of trials did not report results from research biopsies. From an ethics perspective, questions arose about subjecting patients to unnecessary procedures with limited scientific gain and so the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) put together an ethical framework regarding the inclusion of biopsies in clinical trials. The ethical framework addresses three main areas: how to maximise the scientific utility associated with biopsies, how to minimise the participant risk, and how to improve oversight of the process. To help patients and clinical trialists determine whether a research biopsy fulfils the goal of having an overall favourable risk-benefit ratio—and therefore meets ethical justification—the framework explicitly defines the scientific contribution to be expected from a biopsy, categorises participant risk, and outlines when mandatory biopsy may be justified. As a result, the research led to the adoption of standard operation procedures for biopsy acquisition within the National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Network (ETCTN). The idea is that by providing “best practice” guidance, we will minimise the number of patients who undergo unnecessary or non-diagnostic research biopsies as part of their participation in a clinical trial.

What do you hope to achieve as SIR president?

As SIR is a big organisation, I think it’s important that the president not necessarily have a personal agenda but rather, that the executive leadership works cohesively towards multi-year strategies that will drive forward initiatives for the society and specialty. As we begin to celebrate 50 years as a society in 2024, many of the initiatives in the past several years have been focused on establishing a foundation to allow us to be able to compete as a primary medical specialty. Examples of this include the integration of the clinical specialty councils into the governance structure which allows for the voices of our key opinion leaders to be heard and participate in strategic decision-making; the variety of educational products, including the launch of SIR Edge, a new fall 2024 meeting offering; and the ongoing website and user digital experience update. I hope by the end of my time in leadership, I will have contributed to significant infrastructure changes that will set IR and SIR up for success in the coming years.

“We continue to face the challenge of physicians and patients being unaware of the value IR can add to oncology care across the spectrum.”

What was the rationale behind the creation of the SIR Guidelines app?

I became the standards division counsellor for the SIR in 2017, which is how I got involved in the creation of clinical practice guidelines. I’m really proud of the work that committee achieved because, together, we moved the Society to develop the National Academy of Medicine—compliant clinical practice guidelines—and SIR may very well be the first radiology society in the world to do so. This is tremendously important because we’re still jockeying for position on where IR falls in medical treatment algorithms and the acceptance of IR therapies. For us to be viewed as legitimate and competitive as a primary specialty, we needed to put our data through the same methodological scrutiny that is considered the industry gold standard. This was a big step for us in terms of the maturation of the Society and the specialty.

Our first clinical practice guideline was on inferior vena cava filters in the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolic disease. When you read this guideline, you’ll see that it’s different in the sense that it’s question-based with a literature search specific to that question and provides a recommendation that weighs out benefit and harm. Leading the Guidelines Committee was a professional and personal growth experience for me and one of the most rewarding leadership/volunteering experiences I’ve had.

I was also able to work with residents from University of California San Diego, San Diego, USA and some of our early career section members to develop and launch the SIR Guidelines mobile app, which is now used worldwide.We have been downloaded in more than 130 countries and have over 17.5K users! The app gives clinicians point of care access to periprocedural anticoagulation and antibiotic management recommendations for each IR procedure. It returns the information a clinician needs to make a decision in about eight seconds. Ultimately, the guidelines app helps to disseminate information for practice guidance and can help with the adoption and adherence to evidenced-based recommendations.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I enjoy spending time with my family and travelling. We have been to many national parks and we like to hike—some of our more memorable hikes have been Angel’s Landing (Zion National Park) and Half Dome (Yosemite National Park). We are off to Banff this summer. I also like to read, particularly Japanese and Scandinavian murder mysteries, and continue to think about completing another half marathon.