Honoured as the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR)/ British Society of Interventional Radiology (BSIR) travelling professor for 2017–2018, Alex Barnacle delivered the Graham Plant lecture at the BSIR annual meeting (14–16 November 2018, Bournemouth, UK). Titled “Paediatric IR: The adolescent years”, she detailed the years’ successes. Here, she expands on this topic, advocating for the continued growth of paediatric IR as a subspecialty.

Paediatric IR is fast becoming one of our most exciting interventional subspecialties, attracting growing interest from trainees to institutions as a service with a central role in delivering modern healthcare to children.

For too long, it has been considered a highly niche area of medicine, providing supra-specialist care in tertiary paediatric centres but being of little relevance in most other settings. It is thrilling to see the tide turning, with both radiologists and industry recognising that minimally invasive procedures can and should be offered to children, too.

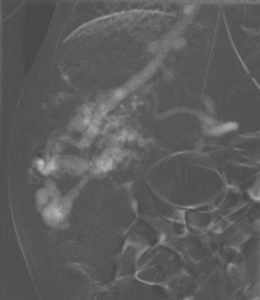

All the factors that make interventional radiology a relevant and exciting specialty apply just as much to children, if not more so. Children and families much prefer ‘keyhole’ treatment options that seem less frightening and allow them to get home sooner. More importantly, minimally invasive image-guided approaches decrease the risks of collateral organ or vessel damage, which is critically important in children with 60 or 70 years of life ahead of them. Our adult IR skills are all applicable in children. But paediatric IR challenges us to take things even further. It forces us to think hard about how to adapt adult kit to fit into small bodies and how to modify our techniques to decrease or avoid radiation burden and shorten procedure times. Examples include the use of carbon dioxide as a contrast agent for abdominal angiography [Figure 1]. This technique allows us to keep both fluid volume and iodinated contrast dose to a minimum in small children. A 4kg baby with a circulating blood volume of only 300ml cannot tolerate much in terms of saline flush volumes or contrast pump injections. The use of CO2 gives diagnostic images for initial angiography and allows us to save iodinated contrast for the selective runs. To control radiation burden, paediatric IRs have become adept at using only ultrasound for many procedures, from mediastinal biopsy to most cryoablation procedures. Such innovation is what attracted many of us into IR in the first place and paediatric IR is a field where, for now at least, the innovative directions seem endless.

Conversely, not everything is so different in children. A baby’s femoral artery can usually tolerate a 4Fr sheath perfectly well and it is rare for us to have to use a 3Fr system for angiography or embolization. In fact, sometimes small is not better. For percutaneous nephrolithotomies, large-calibre tracks (24Fr) allow urologists to achieve complete renal stone retrieval more quickly in small children, minimising procedure times and the associated risks of significant blood loss and hypothermia.

What is different about paediatric IR is the underlying disease processes. As with adult IR, it is critical that we become skilled clinicians and try to understand our patients’ pathologies as thoroughly as the paediatricians and surgeons do. Vascular disease is rare in children but it does exist [Figure 2]. The spectrum of oncological disease is very different to that in adults and it is vital to know which lesions require biopsy, which can be diagnosed from sampling nodal disease and how much tissue is required. The complex genetic abnormalities in neuroblastoma, for instance, mean that 15–20 core needle samples are routinely needed for the complex histological and cytogenetic testing required for risk stratification and treatment planning for these children. Complex congenital diseases expose us to a range of new challenges. Technologies such as intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography allow us to investigate structural abnormalities at a new level and push diagnostic boundaries [Figure 3].

The rewards of paediatric IR are huge. Children rarely complain and once they know they are in a safe environment, they make the most fun and trusting patients. Post-operative rounds are often conducted in the playroom or over a plate of jelly, chips and chocolate. Glitter is an occupational hazard. Adult IRs often tell me it is the thought of the parent interactions that is the most daunting. Sure, conversations with anxious parents can be tough, but so are consults with anxious adult patients and their relatives, and these are skills we can learn with a little practice. I usually find parents to be straightforward and as sympathetic to our concerns as we are to theirs. Their gratitude makes paediatric IR immensely rewarding; it is a great honour to be trusted with their children’s lives. The walls of our offices are littered with ‘first day at school’ photos and news of our small patients’ journeys to adulthood [Figure 4]. Knowing you have given a child the chance of a long, full and healthy life is an extraordinary and frequent privilege.

Paediatric IRs come from a variety of backgrounds. There is only one training number in the UK so, as with adult IR many years ago, training programmes need to be far-sighted, flexible and inventive. Here in the UK, it is more common for paediatric diagnostic radiologists to incorporate IR into their paediatric training to subspecialise in paediatric IR, rather than for those with an adult IR background to turn to paediatrics. There are probably several reasons for this, not least the fact that until recently, most trainees on an IR pathway would have little awareness of any paediatric IR career options. Paediatric diagnostic radiologists have already overcome the fear of working with children, and they know the immense rewards of being involved with children’s care. To them, the world of paediatric IR must seem a little less daunting than it might to, say, an adult vascular radiologist, but I believe this can and will change. In North America, paediatric IR is an increasingly mainstream speciality and one that is now highly competitive, with over 20 specialist paediatric IR training schemes in the USA and Canada. The Society for Pediatric Interventional Radiology is an enthusiastic and highly professional organisation, drawing the paediatric IR community together from all around the globe. This year’s meeting is in Amsterdam and I would encourage IRs to attend.

There are currently fewer than 15 consultant radiologists in the UK who have paediatric IR as a major part of their job plan. But it would be naïve to suggest that paediatric IR is only delivered by those few. A high proportion of those reading this will have been involved in paediatric cases in their career, from relatively routine drain insertions through to emergency embolisations in desperate circumstances. It would be unrealistic to expect all IR procedures in children to be delivered by subspecialists and it is vital that we develop a network of education and support so that all IRs know who to call for advice and support when a challenging case arises. In parallel, it is imperative that we drive forward the development of a wider paediatric IR service in this country. The Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) and the British Society of Interventional Radiologists (BSIR) are taking this challenge seriously; together with the other Colleges, we are surveying services across the UK to identify areas of greatest need and then lobby for more jobs and greater funding.

I had the honour of being the RCR/BSIR travelling professor for 2017–2018. It was a fantastic year. I visited 15 training schemes, from Aberdeen to Plymouth, and met an extraordinary number of trainees fired up by the possibilities of paediatric IR. Many have subsequently come to visit our centre and I have absolute confidence that most will follow it through to develop and shape rewarding careers with a paediatric IR focus. Only a few years ago, our paediatric IR fellowship post lay unfilled, but now we have trainees clamouring for similar posts around the UK. Over the last couple of years, it has become increasingly clear that a forum is needed to feed trainees’ interest and to grow a support network for both adult and paediatric IRs working in this challenging and emotive field. A Paediatric IR UK meeting grew out of this and at our inaugural meeting in November 2018, we welcomed 78 trainees, IRs and industry representatives for a memorable day of paediatric IR teaching and sharing that we will be building on in June 2019. Follow us on Twitter @PaediatricIR for details.

I have watched with pride and excitement as its influence has grown over the last ten years and I have no doubt that its future here in the UK is very bright indeed.

Alex Barnacle is a consultant paediatric interventional radiologist in the Department of Radiology at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children (GOSH), London, UK. She is on Twitter as @BarnacleAlex.